In 1727 Antonius Braun, with the help of the French mechanic Philippe Weiringe, created the first calculating machine for the Viennese Court. This calculating machine is called the Leopold-Braun-Weiringer calculating machine. A copy is in the German Museum in Munich.

Modern scientists call these first calculating machines revolutionary inventions of their time. They became the basis for the development of computer technology and scientific research in the fields of mathematics and physics.

The question is still the same: Where in 1727 did such knowledge come from, enabling the creation of incredibly complex mechanical devices?

Incidentally, the first mechanical calculator was invented even earlier, in 1623.

History of mechanical calculators:

Wilhelm Schickard (1592-1635) created a calculating machine for his idol astronomer Jan Johannes Kepler (1571- 1630). It was 6-digit and had an adder for decimal numbers. The unit for recording intermediate operations was practically the embryo of RAM. In 1623, W. Schickard sent this machine by mail to J. Kepler. Unfortunately, a fire at the post office destroys the machine. In the surviving letters to J. Kepler there is a detailed sketch and description of the machine. According to it, in the second half of XX century the machine was built. And it works.

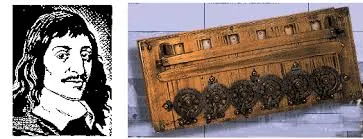

In 1642, 19-year-old Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) invented a computing machine for his father E. Pascal (1588-1651). It had a device that (mechanically) added and subtracted 6 to 8-digit numbers. This machine was supposed to facilitate calculations in trade transactions, as well as in the calculation of taxes. Structurally, Pascal’s machine was actually a cash register, only without a drawer for money.

In 1672 Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) built essentially the first arithmometer, which in addition to the operations of addition (and subtraction) could already perform the operations of multiplication and division. In 1673 Leibniz’s machine was shown to the members of the Royal Scientific Society in London. The main part of the machine consisted of stepped rollers on which 2-digit numbers were dialed.

In 1631 W. Schickard himself became professor of astronomy at Tübingen University. Recall that Pascal’s snail is named after Etienne Pascal (1588-1651), who was fond of mathematics. Blaise Pascal built more than 70 copies of his machine. Some of them have survived and still work.

In 1694, Leibniz improved his machine and it became a 12-digit machine. Building a computing machine was no accident for Leibniz – Leibniz had the idea of building a universal logical algorithm that would allow him to prove or disprove any proposition of any formalized science. One of the first steps toward constructing such an algorithm was to become a computing machine.

In 1673 the watchmaker and mechanic of King Louis XIV of France (1638-1715), René Grieux de Rauvin, who lived at the end of the 17th century, published a small book in which he announced the invention of an arithmetical computing machine. Five years later (in 1678) he gave a description of this machine in Le Journal des Scavans. According to René Girier, this machine could both add and multiply. Between 1673 and 1681, René Girier demonstrated his machine in both France and Holland.

Video below: Calculator from 1727: Antonius Braun’s calculating machine

По материалам: http://www.planet-today.com/2023/05/history-of-first-calculating-machines.html